Army

Hospital Trains

By Robert S. Gillespie, MD, MPH

Text and author’s photos copyright 2006 by Robert S. Gillespie.

<>Most of the

RailwaySurgery.org website chronicles railway medicine in the civilian

world. This page tells how the U.S. Army used trains for medical

evacuation and treatment. For a much more detailed treatment,

read Trains in White, Dr. Gillespie's comprehensive article on

the history of Army hospital

trains, published in Railroads and World War

II, a November

2007 special edition of Classic

Trains magazine by Kalmbach Publishing.

See the information below and a reprint of a 1945 article

on hospital trains.

A Brief Summary of Wartime Medical Evacuation by Train

The Civil War (1861-1865)

§ First wartime use of trains

§ Varied from improvised boxcars to purpose-built cars funded by relief organizations

The Spanish-American War (1898)

§ A single train of Pullman tourist sleepers was used

World War I (1914-1918)

§ Custom-built unit cars and leased passenger cars used

World War II (1939-1945)

§ Large-scale use of hospital trains; hundreds of cars and countless trains

§ Additional leased sleeper and chair cars also used

§ Medical air transportation in its infancy

§ After the war; most were sold; many were converted to passenger coaches or dining cars to replace older equipment worn out from wartime overuse

The Korean War (1950-1953)

§ Remaining hospital cars from WWII sent to Korea; replacements ordered

§ Hospital trains played critical role, but use of air evacuation techniques increased dramatically

§ The last conflict in which hospital trains were used

§ Replacement cars were stored, never used, and later sold

World War II

Hospital trains reached their pinnacle during World War II, although they were used in many conflicts. The number, complexity and resources devoted to hospital trains during this war far exceed that of any other period. This page focuses on domestic applications for injured troops coming home. Countless other hospital trains were used to carry troops in the various theatres of the war, often using a wide variety of locally available equipment.

Some web browsers do not display images well. These are good quality pictures. If they look fuzzy to you, try an alternative browser, or right click, choose “save picture” and then re-open them with an image viewing program.

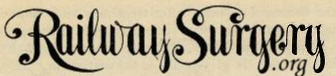

This World War II-era ad from the New York Central gives a detailed description of a typical car on an Army hospital train.

The Army experimented with several different designs of hospital cars. Notice the diagram at the very bottom of the advertisement above, showing how different cars were arranged in a hospital train. Types of cars included:

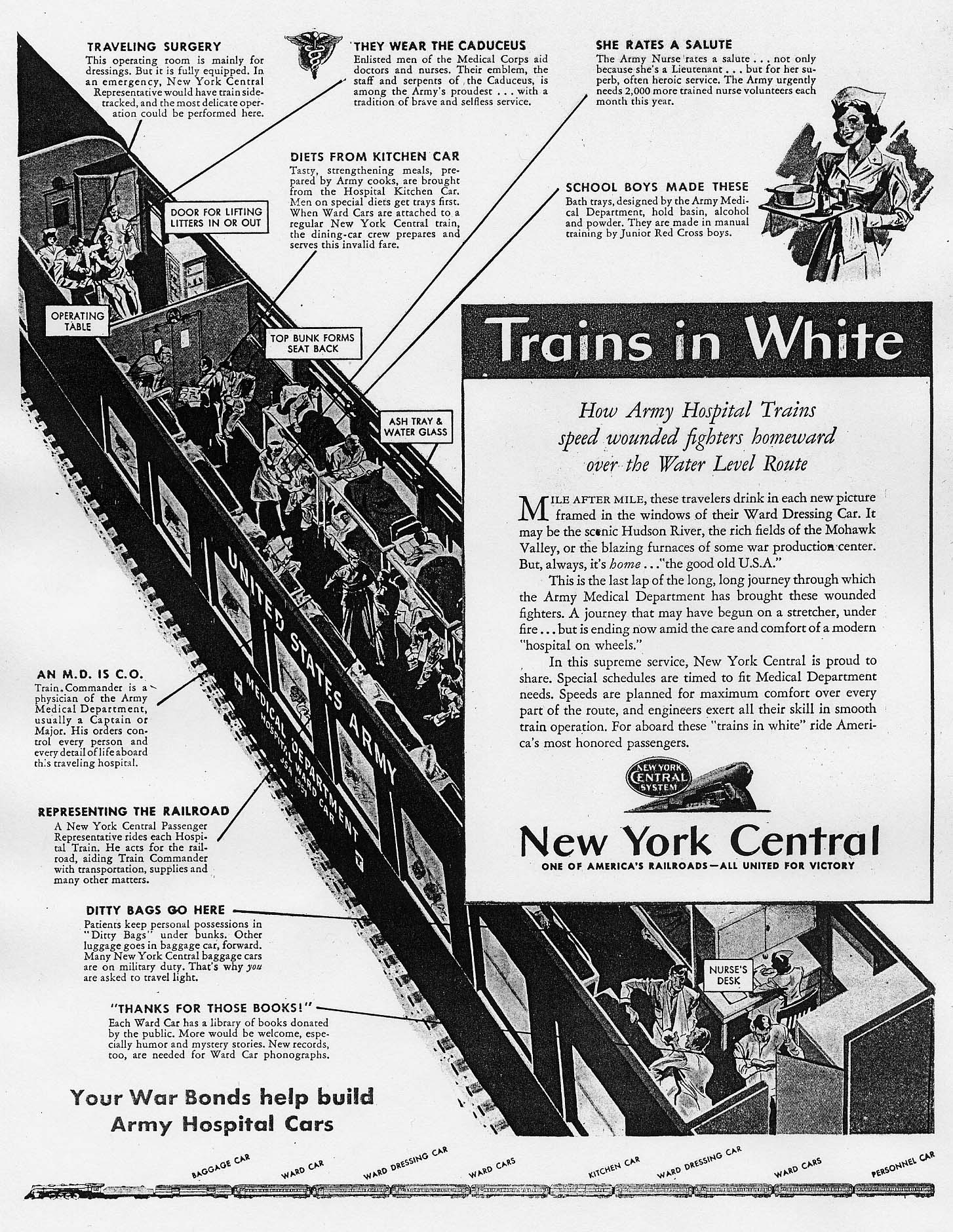

§ Ward Cars: Like a hospital ward, these cars contained berths to hold patients.

§ Ward Dressing Cars: Ward cars with a “dressing room” at one end. The dressing room was a clean area used to change dressings. It could also serve as an operating room for emergency surgery.

§ Kitchen Cars: These cars held kitchens and food storage areas to prepare meals for patients.

§ Unit Cars: A hybrid design that served as a self-contained “unit,” these cars typically had a ward area with berths, a small kitchen, and a dressing room. The unit car became the most popular design, because of its flexibility.

As patients arrived from overseas on huge hospital ships, they were moved to hospital trains waiting at the ports. (During WWII, planes were seldom used for medical evacuation. The supply was limited and they were all needed for other duties. In addition, medical air transportation was a new concept which was not well developed.) The patients traveled by train to the military hospital closest to their home of record, or best specialized for their type of injury, to continue treatment and recovery. Often a long hospital train would depart from a port, using a kitchen car to provide all meals for the whole train. Along the way, some of the unit cars would be removed, to route to other destinations. Once they detached from the “mother train,” these unit cars took advantage of their independent capabilities and used their smaller onboard kitchens to provide the meals.

By the end of World War II, the U.S. Army owned 202 unit cars, 80 ward cars, 38 ward dressing cars and 60 kitchen cars, a total of 380 cars.

Below: Floor plan diagrams for three types of hospital cars.

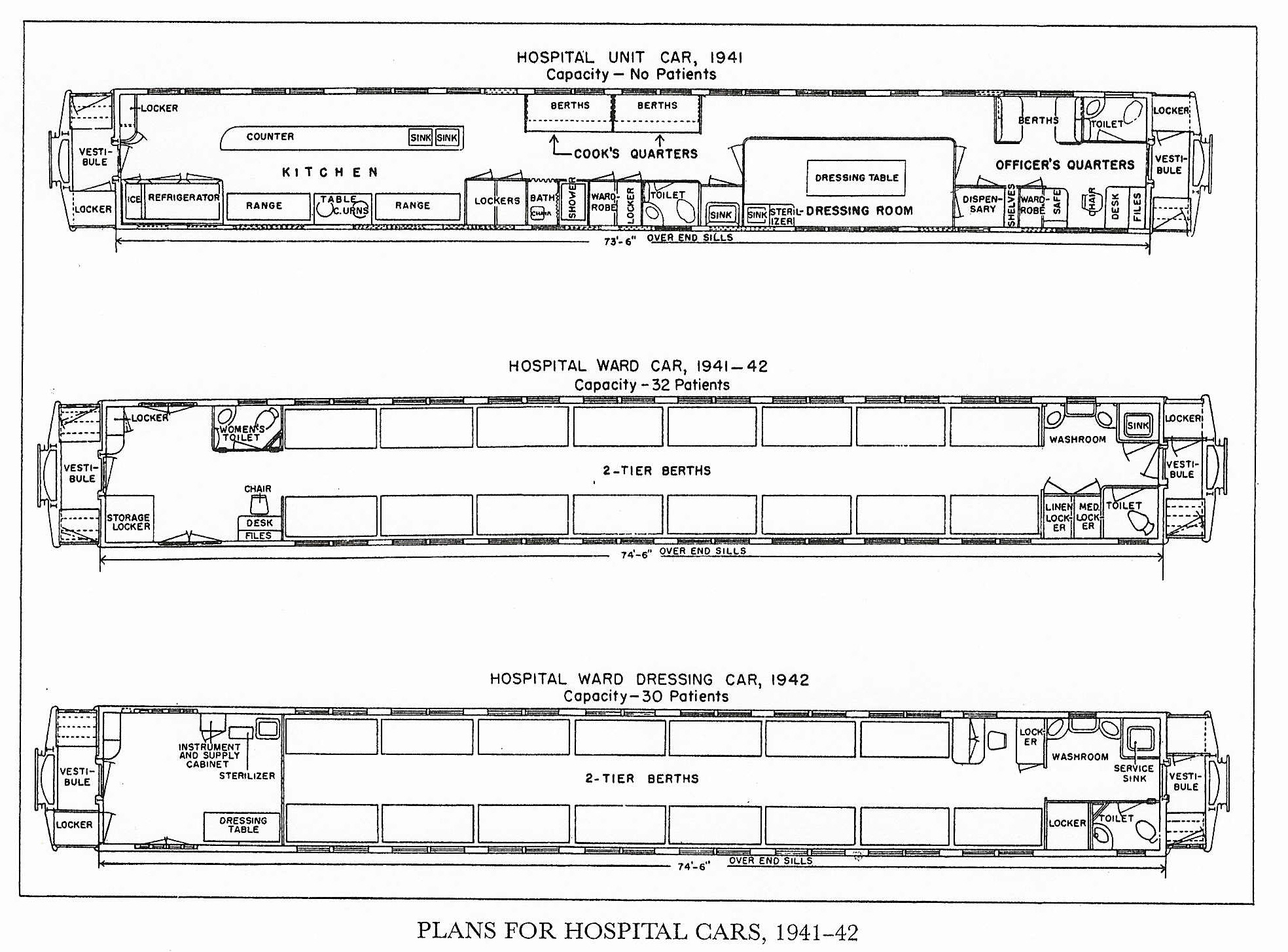

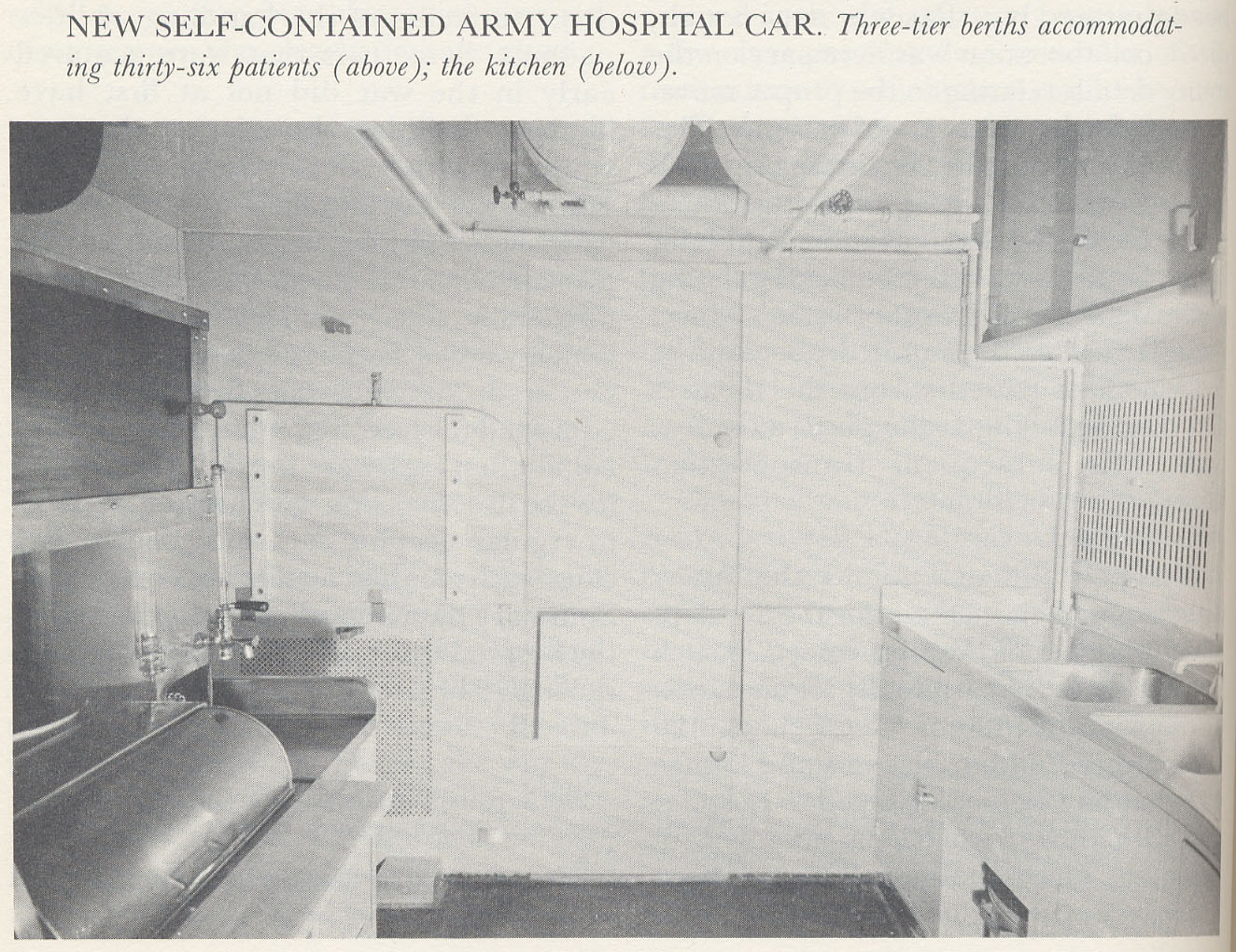

Below: Interior view of a hospital car with 36 berths and a kitchen at one end.

From: Wardlow, Chester. The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training, and Supply. (Series: United States Army in World War II.

Subseries: The Technical Services.) Washington DC: Department of the Army, 1956, p. 72. Not copyrighted.

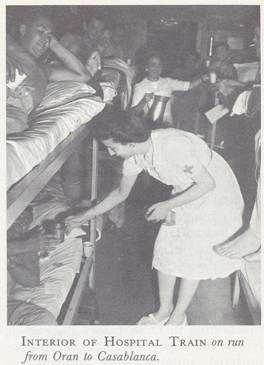

From: Wiltse, Charles M. The Medical Department: Medical Service in the Mediterranean and Minor Theaters. (Series: United States Army in World War II. Subseries: The Technical Services.) Washington DC: Department of the Army, 1965, p. 207. Not copyrighted.

Above, a scene from a busy hospital train during World War II.

Photo by the author.

Above: Hospital car number 89531 at the Army Medical Museum at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas. This is a unit car with 27 patient berths, a receiving/dressing change area, a small kitchen, quarters for a crew of 6, a shower and restrooms. The car resembles a section sleeper, but the beds are stacked in tiers of three, without walls between the sections. Cars such as this provided the highest level of care to seriously injured soldiers, attended by doctors, nurses and medics on board.

Photo by the author.

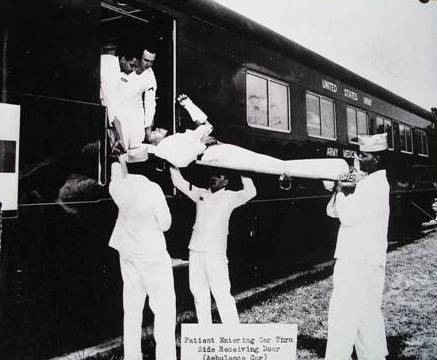

The hospital cars had large side doors to facilitate loading and unloading patients, as shown in the undated photos below.

Note the canvas stretcher (“litter” in military terminology) propped against the car.

Photo by the author.

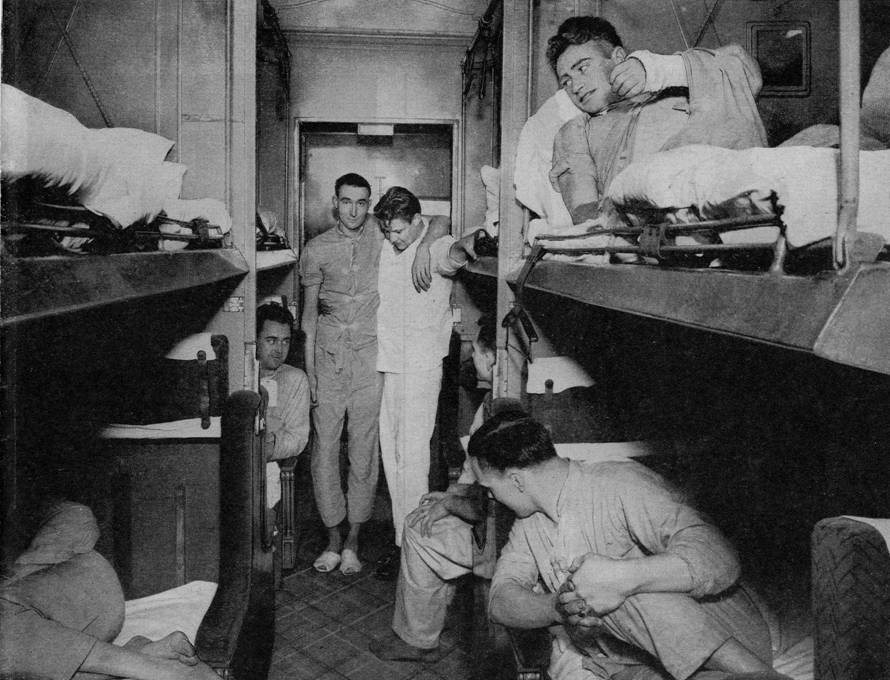

This composite photo, above, shows the interior of the Army Medical Museum’s unit car. It has 27 berths in the center of the car, with a kitchen, receiving and dressing area at one end, and crew quarters and restrooms at the other end. (In the actual

museum car, some of the bunks have been removed to provide space for other exhibits.) Below: Berths on the hospital cars were compact but comfortable, and certainly lavish compared to battlefield conditions. During WWII, the Army mandated that all its hospital cars have air conditioning, quite a luxury at that time.

Photo by the author.

Photo by the author.

During the daytime, the crew could fold away the berths to create sitting areas.

At one end of the unit car is a receiving/dressing change area with a desk and sink. Just beyond that is a small kitchen. (Photos by the author.)

Photo by the author.

The Army found that railroad dining-car crews did not adapt to hospital life well, being unfamiliar with special medical diets and unwilling to provide meals around the clock. Eventually, the Army opted to provide its own food service using baggage cars converted to kitchens, and purpose-built kitchen cars such as #89601, above. This car is fully equipped with a huge coal-fired stove and oven, iceboxes, pantries, sinks, work areas and a shower. It has self-contained hot and cold water and electrical systems, so it will function whether it is attached to a train or not. Meals would be prepared here and taken to patients in other cars on trays; the Army never intended for passengers to pass through the kitchen cafeteria-style.

The kitchen car above belongs to the Northwest Railway Museum in Snoqualmie, Washington. It has much in common with unit car #89531 from the Army Medical Museum shown earlier on this page. Both cars came from the St. Louis Car Co. in 1953, built for the U.S. Army Transportation Corps. Both cars were built to replace nearly identical WWII-vintage equipment sent overseas during the Korean War. Both cars never actually saw service; they were stored, retired unused, and sold to private concerns before the museums acquired them.

When the Army needed more capacity than the fleet of hospital cars permitted, it leased section sleepers and chair cars from the railroads. These cars could carry soldiers who were more ambulatory and did not require as much care. Pullman took out this ad in 1945 to show its contribution to the war effort. The bunk layout is similar to the hospital cars, but most hospital cars had three tiers instead of two, and the hospital cars had large side doors for loading from litters (stretchers). The section sleeper cannot accommodate litters, because the path to the door involves a narrow offset hallway with several 90-degree turns which a litter cannot navigate.

Hospital Cars vs. Troop Sleepers

Railroad buffs often ask how the hospital cars were related to another widespread WWII railroad car, the Army troop sleepers.

The answer is that they had little in common, as shown in the comparison below.

|

|

Hospital Car |

Troop Sleeper |

|

Purpose |

Carry injured troops to hospital facilities |

Carry healthy, active troops to and from bases |

|

Design base |

Built from passenger-car shells |

Based on freight car design (they were essentially glorified boxcars) |

|

Berths |

Tiers of 2 or 3 |

Tiers of 3 |

|

Berth layout |

Parallel to long axis of car (Ideal for moving patients on/off litters, and for medics to observe all patients in a single line of sight) |

Perpendicular to long axis of car (It would be impossible to carry litters to the berths, and difficult to observe patients with this configuration) |

|

Air conditioning |

Always |

Never |

|

Medical facilities |

Many cars equipped with dressing-change facilities, sterilizers and other equipment |

None |

|

Kitchen facilities |

In some cars |

No (always used separate kitchen car) |

The Future

Hospital trains could be very useful in times of natural or man-made disasters. Medical care and evacuation following Hurricane Katrina was a complete fiasco, with patients being moved on baggage carts or being left to die on the tarmac. Poorly equipped doctors and medics struggled to treat patients in the airport terminal, a building never intended to serve as a medical facility. A well-designed and carefully pre-positioned medical train could have brought supplies, personnel and hospital-grade facilities to the scene quickly and efficiently. Perhaps it is time to develop a hospital train for the 21st century. David Kelly develops this idea in great detail at Emergencyrailconcepts.org.

Where to Learn More

§ Visit the Army Medical Museum in San Antonio, Texas, to see their unit car on display, with many other artifacts and interpretive information.

§ Visit the Northwest Railway Museum in Snoqualmie, Washington, to see their kitchen car.

§ Visit Emergencyrailconcepts.org to learn more about possible modern uses of hospital trains to respond to national emergencies.

§ Read Mercy Trains by James Y. Harvey, the definitive history of the Australian army hospital train experience. It is available through the Australian Railway Historical Society, New South Wales Division (www.arhsnsw.com.au).

§ Read these two books from the Army’s exhaustive history of World War II:

□ Wardlow, Chester. The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training, and Supply. (Series: United States Army in World War II. Subseries: The Technical Services.) Washington DC: Department of the Army, 1956.

□ Wiltse, Charles M. The Medical Department: Medical Service in the Mediterranean and Minor Theaters. (Series: United States Army in World War II. Subseries: The Technical Services.) Washington DC: Department of the Army, 1965.

§ Greatwardifferent.com has some interesting period articles about World War I hospital trains in Europe. See On the Great White Hospital Train and Train de Bargigli.

We hope you enjoyed this page! Please send your comments to robert @ railwaysurgery.org.

RailwaySurgery.org - Site Map

Home A Brief History of Railway Surgery A Detailed History of Railway Surgery Railway Surgeons and Vision/Hearing Testing

Army Hospital Trains List of Railroad Hospitals Image Gallery Become a Railway Surgeon Archives Where to Learn More About Us/Site News Blog