Testing Vision and Hearing

by Robert S. Gillespie, MD, MPH

Copyright 2006

Most nineteenth-century doctors believed colorblindness to be an extremely rare condition, despite studies as early as 1854 suggesting it affected 5 percent of the population. Railroad officials assumed that a colorblind engineer or signalman would perform poorly and soon be discovered or fired. A serious railway accident in Sweden in 1875 halted such complacency. The incident, attributed to a colorblind employee misreading a signal, drew widespread public attention. A Swedish doctor, Frithiof Holmgren, developed a method to test color vision and applied it to the entire staff of the railway. Holmgren surprised officials by finding that 4.8 percent were colorblind—including many successful senior employees. Swedish officials promptly enacted laws requiring vision testing for all railway workers. In the U.S., only a few states passed such laws, but many railway managers took action. Ophthalmologist John Weeks reported in 1894 that two-thirds of the railroads serving New York City had voluntarily adopted such programs.

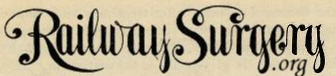

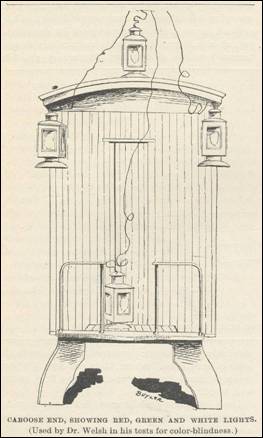

Holmgren’s test required subjects to match colors among 150 objects such as squares of colored paper or skeins of yarn. Other physicians developed many elaborate testing methods, often using colored lights or flags to simulate working conditions on railroads. One even built a full-size mockup of the end of a caboose in his office. However, a railroad planning to test its entire workforce needed an inexpensive, portable and fast technique that did not require a physician to examine every single employee. When the Pennsylvania Railroad began system-wide color vision testing in 1880, officials commissioned Dr. William Thomson to develop such a solution. Thomson simplified Holmgren’s test into a set of 40 standardized, numbered skeins of colored yarn attached to a ruler-like board, which became known as Thomson’s Stick. The examiner handed the subject a sample of yarn and asked him to choose from the stick other yarns similar in color. The examiner recorded the numbers of the colors the subject chose. Railroad supervisors could administer the test after minimal training, and each test required only two to three minutes. Those who passed the test required no additional study. Employees who did not pass were referred to the railway surgeon for retesting and further evaluation. This allowed the doctors to focus on the small number of employees with questionable results, without having to spend time examining the vast majority who had normal color vision. The railway surgeon could tell which colors the employee had chosen by reviewing the numbers on the test record, often making a preliminary diagnosis even before examining the employee. Initial tests on the Pennsylvania showed 4.2 percent of employees to have color vision defects, similar to findings in European studies.

The Pennsylvania, as with other railroads, also tested visual acuity (sharpness), using the familiar Snellen chart with a large “E” at the top. The railroad tested hearing using a pocket watch. Employees who could hear the watch ticking from five feet away passed the test. These primitive tests had shortcomings, but they formed one of the earliest attempts to use medical screening as means to enhance workplace safety, and one of the first applications of large-scale health screening using a standardized test administered by trained, non-medical personnel. Such techniques, fiercely controversial then, find widespread application today. Examples include hearing tests given in elementary schools, or visual acuity and color vision tests administered in drivers’ licensing offices--the direct descendents of railroad vision testing.

Images

1 and 2. Dr. Emmet Welsh of Grand Rapids, Michigan, devised a realistic but hardly portable method of testing color vision (above left). His caboose mockup used electric lanterns of different colors. At right is shown a schematic for a similar system, minus the caboose.

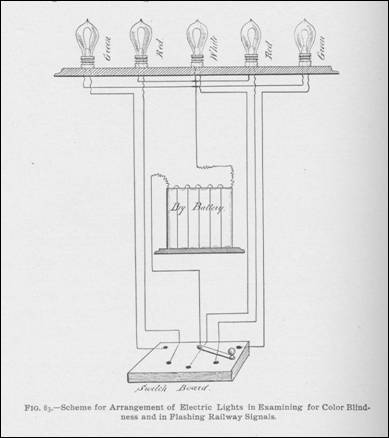

3 and 4. One effort at a portable color-vision test used kerosene lanterns inside a case with colored filters (above left). As color vision testing became more of a concern to railroads, some doctors wrote books about it, such as this 1905 manual by Dr. Jennings (above right).

5. The color vision test devised by Dr. Thomson, widely known as Thomson’s Stick (above), was simple, practical and economical, making it very popular. The stick contains 40 numbered skeins of yarn (colors shown in table below). Odd-numbered samples are of the test colors while even-numbered ones are of different colors. The examiner would give the subject one of the loose skeins seen at the bottom of the photo, and ask him to select skeins of similar color from the stick. Choosing any of the neutral or contrasting colors (even-numbered skeins) is incorrect. A colorblind individual would not be able to distinguish the test colors from the neutral/contrasting colors. A major limitation of this test is that the subject can “cheat” and easily pass if he knows the “secret” – choose only the odd numbers!

|

Skein numbers |

Test colors – odd numbers (correct choices) |

Neutral or contrasting colors – even numbers (incorrect choices) |

|

1-20 |

Green |

Gray; tan, light brown |

|

21-30 |

Rose |

Blue |

|

31-40 |

Red |

Brown, sage, dark olive |

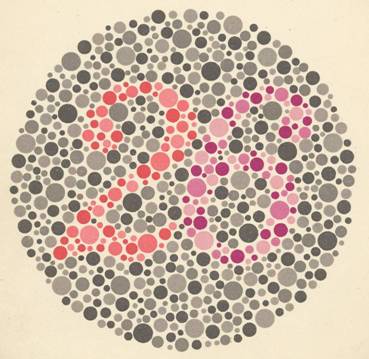

6. Thomson’s Stick is no longer used. A modern test for color vision uses a series of plates such as this one (above) devised by Dr. Ishihara. A subject with normal color vision can read the number 26 in the above plate, but a person with colorblindness will see only a field of gray dots.

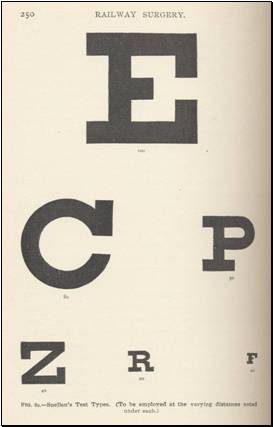

7. Some things never change. The basic principle of the Snellen vision chart (above) remains familiar to almost everyone. Similar charts remain in widespread use today, more than a century after this one was published. These charts test only visual acuity (ability to see fine detail at a certain distance) and not color vision.

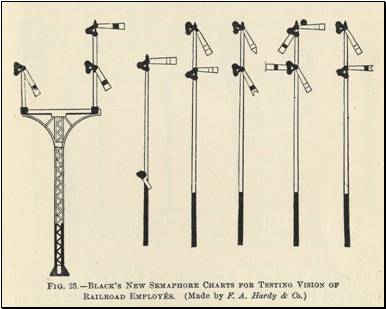

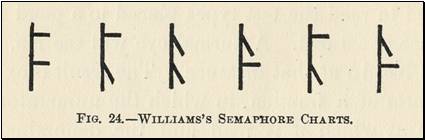

8. These charts (above) attempted to test visual acuity in a form specific to railroad work. They represented the semaphore-type signals used alongside railroad tracks as “traffic lights” to direct train movements. Incorrect reading of the signals could cause disastrous accidents.

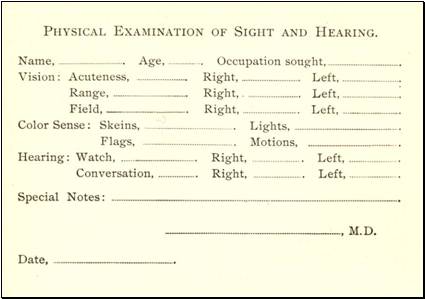

9. The railway surgeon would issue

a card such as this one (above) with the results of an employee’s vision and

hearing tests.

Visit the Archive to read the 1896 article The Value of Examinations of Sight, Color, Sense and Hearing in Railway Employes (The Railway Surgeon, Sept. 22, 1896).

Image Sources

Information not available if no source listed.

1. Welsh, D. Emmett. Color blindness. The Railway Surgeon. 1894;1(1):8-10.

2. Herrick, Clinton B. Railway Surgery: A Handbook on the Management of Injuries. New York: William Wood and Co., 1899, p. 252.

4. Jennings, J. Ellis. Color-vision and color-blindness: A practical manual for railway surgeons. Philadelphia , PA: F.A. Davis, 1897.

5. Author’s collection.

7. Herrick, p. 249.

9. Herrick, p. 252.

RailwaySurgery.org - Site Map

Home A Brief History of Railway Surgery A Detailed History of Railway Surgery Railway Surgeons and Vision/Hearing Testing

List of Railroad Hospitals Image Gallery Become a Railway Surgeon Archives Where to Learn More About Us/Site News Blog